The nature of making a customised product is that products usually need to go through an engineering and specification phase prior to commencing manufacturing. This will often involve quoting, design, product configuration, bills of materials and routings, development of shop drawings, CNC programing and preparation of quality documentation. For printing businesses, the Pre-press process is very similar to engineering and many of the suggestions I make below can and have been applied by the TXM team to pre-press processes.

Unfortunately in many cases these engineering processes can take longer than the actual manufacturing process and the lead time can be unpredictable. While sophisticated planning and and job tracking software and, we would hope, lean visual controls keep track of what is happening n the production flows, such controls rarely exist in the Engineering department. So how can you achieve shorter more consistent lead times in Engineering?

What is the “Product” of Engineering

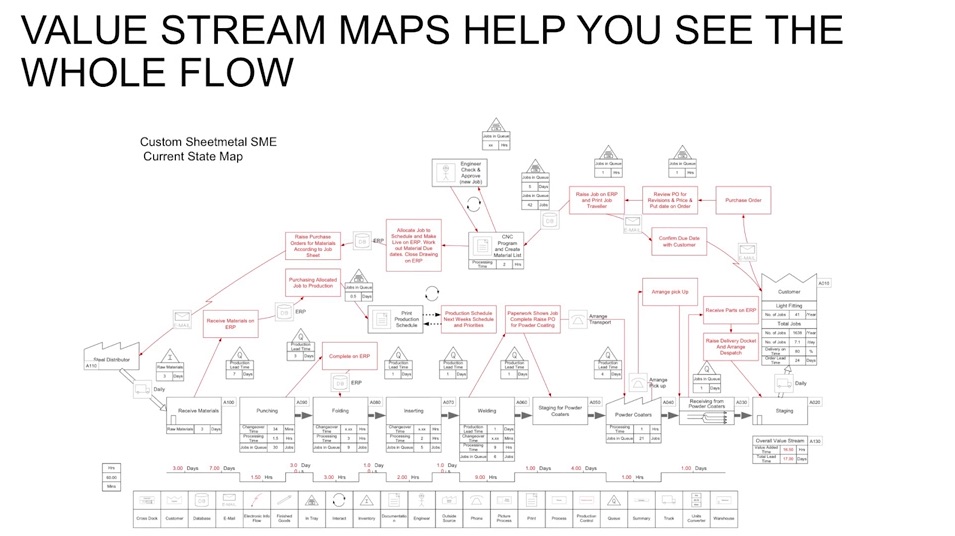

The process of understanding your engineering process is very similar to understanding your production process. You need to map the process using a value stream map. However there are some subtle differences.

Firstly, a typical value stream map has product and information flows. Engineering handles information, there is no physical product in most cases. We therefore define the “product” as the design information. Starting with a customer specification or drawing, this “product” will gradually transform in to a set of drawings, CNC programs and documents that enable the physical product to be manufactured. Value adding is therefore defined as processes that transform that initial customer data in to a form that can be used to produce the product.

Define the Boundaries of Your Process

Again, like value stream mapping a product, you need to define your value stream. This means deciding which stream you will map and where that map starts and ends. For example, do you consider the quoting process or does the process just start when the customer places an order and agrees the final specification? What about original design or R&D, should it be included or do you limit your value stream to production engineering? It is very easy to get very complex and end up with a value stream that goes right around your room, so we suggest that you break these elements down and treat them separately if you can. Then you may find that you have parallel value streams, for example the development of the actual design, drawings and programs and the preparation of compliance documentation. These may run in parallel through completely different people. In our experience one process will tend to drive the overall engineering activity. This is usually the most complex and time consuming process (usually the actual production engineering) and therefore it is usually best to start on that process.

You may also find it necessary to segment types of jobs, for example completely new jobs or repeat jobs, complex jobs and simple jobs. This can be inexact, but look for the patterns in the workload through engineering and analyse the data of the actual jobs that you do, don’t go off peoples opinions or gut feel.

Mapping the Current State

Mapping the current state is again similar to mapping a product flow. You need to first define what the customer needs. This usually requires defining a unit of measure. In most cases this will be the number of jobs or orders processed, but can sometimes be the number of engineering or programming hours.

Define your processes – these are the steps that you go through to add value to the engineering information. Make sure to identify where multiple tasks are completed by the same person or team at the same time or in sequence. These are usually work elements of a single process.

So, for example if an engineer reviews the customer drawing, creates a specification and creates a BOM and Routing as a single step this is one process, but If he or she just, for example reviews the customer drawing and information and passes it on to someone else to create the BOM and Routing, this would be two steps. A process occurs when the flow of the design stops and requires an additional piece of information to move it on. The next step is therefore to manage the information flow, which is the information and instructions to move the information required to the next step of the process.

Compared to production, these information flows can be very murky and informal and often subject to the wide range of different roles and priorities that an engineer is managing. Finally you need to gather data on each process. How long does it take to complete? What are the backlogs and lead times at each step of the process? What enforced delays exist and are there any “changeover times” involved in going from one task to another.

Generally the best place to find this data is from histories of past jobs. Once you have gathered this information, you can complete your value stream map and get an understanding of the lead time in your engineering process and the value and non value added time involved in that lead time – expect to be surprised at how much non-value added time there is.

Create Your Future State

The current state map is interesting, but it is in developing the future state that you will really start to come up with solutions to your lead-time problems. Avoid the temptation to dive in and brainstorm. At TXM we use our “Seven Steps to the Future State”. This steps your team through a series of questions that enable you to see your engineering process with a different set of eyes.

These questions include what is your takt tme? This is an interesting and challenging question for engineering, but forces you to confront the need to match your engineering resources to the needs of your market and to manage your “production capacity” for engineering. Other critical questions are whether processes can be combined to create “work cells” or eliminated altogether. Often engineering processes contain a lot of unnecessary handoffs, signatures and checking.

Simplifying or eliminating these can frequently remove large amounts of lead-time. Where processes cannot be combined, tools to control the flow of work between processes are essential. These can help visualise the flow of information and avoid backlogs building up. Finally controlling the rate of work release in to engineering will reduce lead times and highlight problems quickly before they lead to late deliveries.

Implementing the Plan

Your future state will provide you with a shopping list of improvements to make and we suggest organising these in to an A3 plan. This will outline what your current state is, where you want to get to in your future state, what your objectives are in terms of improvement metrics and how you plan to get there, your action plan. Aim to have an action plan that can be completed in 3-6 months are longer plans frequently lose momentum. You then need to assign responsibilities and plan to review and update your plan with the engineering team every week.

Getting Engineers to Change

I am Engineer myself and compared to operators we can be a stubborn and opinionated bunch. The secrets to achieving a successful change are, however similar to those in your manufacturing process.

- Make sure you involve all the key stakeholders in the mapping process. This means all the individuals involved in the various steps of engineering as well as “internal customers and suppliers”, particularly sales (or customer service) and operations.

- Usually the value stream map will start at the external customer and finish with the job ready to start production, so make sure you cover all the people along that stream.

- Ensure that these key people are engaged right through the process and don’t drop in and out of the process and sabotage it without understanding the full picture.

- Make it clear that everyone is welcome to have an input, but that everyone must respect everyone else’s input.

- Set a clear goal that everyone understands the importance of. For example, set a specific goal for lead time reduction and relate that directly to the needs of your market and customers Make it clear that the process is not about making people work harder (they are already working hard), but eliminating waste and inefficiency and that no-one’s job is threatened by the improvement process.

- Finally Set clear metrics with challenging, but realistic improvement goals and keep driving these. This will keep people focused on the overall purpose of the improvement rather than getting bogged down in the detail of the tools.